The Gateway of the Gods

If you could step back in time more than 2,500 years and sail along the slow, brown waters of the Euphrates River, you would see a shimmering city on the horizon. Massive defensive walls, taller than any you’ve ever seen, rise in layers, glistening with sun-baked mudbrick and glazed tiles. The city’s name? Babylon — in Akkadian, Bāb-ilim, meaning “The Gate of the Gods.”

Babylon’s origins were humble. Around 2300 BCE, it was little more than a modest settlement tucked between the riverbanks of Mesopotamia. But its location was strategic — right along the trade arteries connecting the Persian Gulf to Anatolia and the Levant. Over centuries, this dusty town became the beating heart of a superpower.

The first golden age began under King Hammurabi (1792–1750 BCE). He was not only a conqueror but a shrewd administrator. Under his leadership, Babylon became the center of an empire that stretched far beyond its modest beginnings. Hammurabi’s most enduring legacy is his famous Code of Laws, engraved on a basalt stele. Its 282 laws ranged from property disputes to trade regulations, and yes, that famous line: “An eye for an eye, a tooth for a tooth.”

Hammurabi turned Babylon into both a military fortress and a religious center. The city was dominated by towering temples dedicated to the gods, particularly Marduk, the city’s patron deity. Marduk’s temple, the Esagila, was more than just a religious building — it was a symbol of Babylonian cosmic order, a reminder that the city was not just any city, but the seat of divine authority.

The Age of Nebuchadnezzar II

Fast-forward nearly a thousand years. By the 7th century BCE, Babylon had fallen into and out of foreign hands several times — Assyrians, Elamites, and others had taken their turn controlling it. But then came the Chaldean dynasty, and with it, Babylon’s most famous ruler: Nebuchadnezzar II (reigned 605–562 BCE).

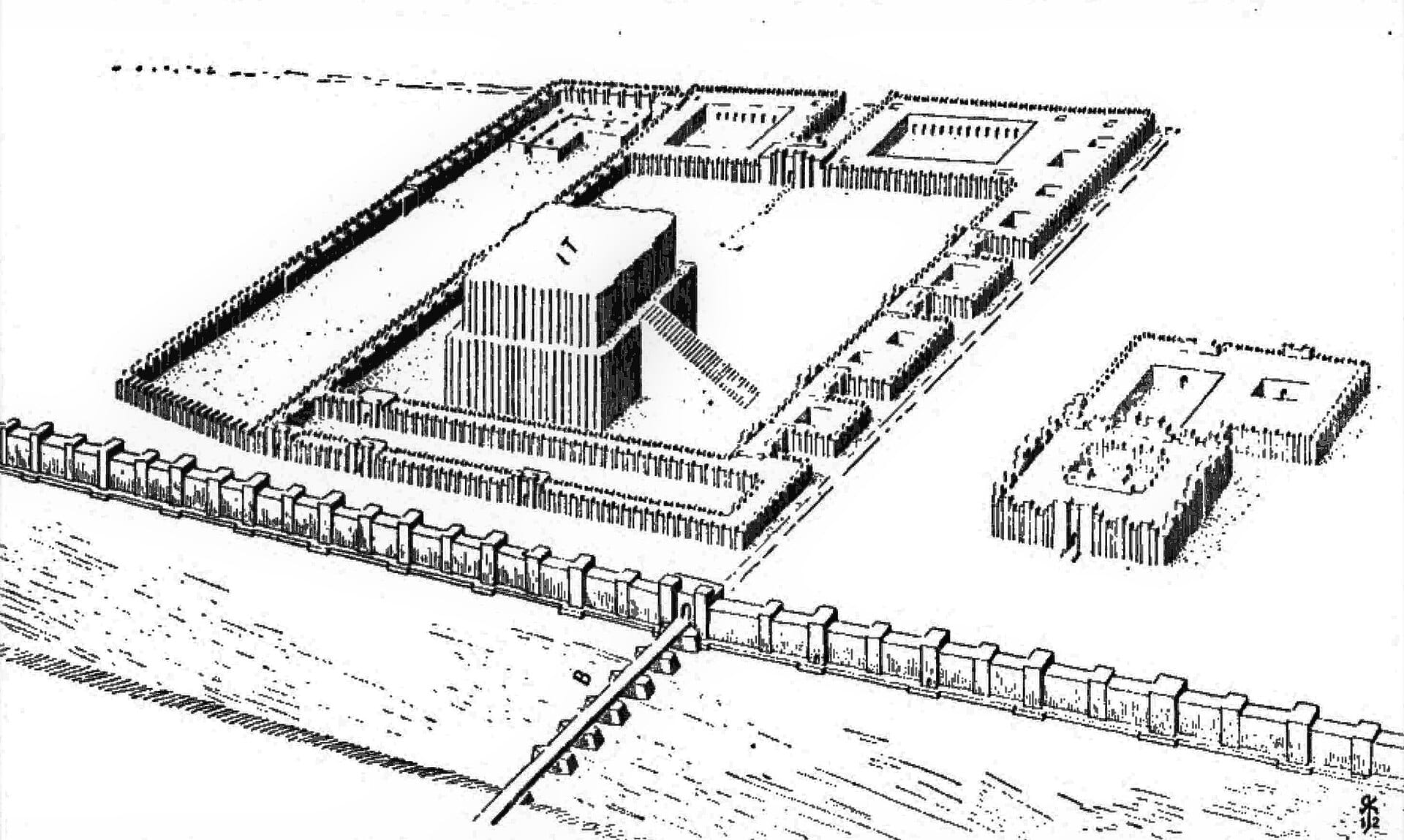

Nebuchadnezzar was a man obsessed with two things: military power and monumental architecture. Under his rule, Babylon reached its zenith, becoming the largest city in the known world at the time. Ancient writers claimed its walls were so thick that chariots could race along their tops. Archaeologists have confirmed sections of the fortifications were indeed massive — in some places more than 20 meters thick.

But Nebuchadnezzar’s reign is remembered most vividly for a wonder that may or may not have existed: the Hanging Gardens of Babylon.

According to legend, Nebuchadnezzar built these gardens for his wife, Amytis of Media, who missed the green hills of her homeland. If the accounts are true, the gardens were an engineering marvel — a series of lush terraces planted with exotic trees, flowers, and vines, irrigated by a complex system that lifted water from the Euphrates. Greek historians like Strabo and Philo of Byzantium described them as a paradise suspended in the air.

Whether the Hanging Gardens truly stood in Babylon or were a later myth (possibly confused with gardens in Nineveh) is still debated, but in the ancient imagination, they became a symbol of opulence, love, and technical genius.

Life Inside the Walls

Babylon wasn’t just for kings and monuments — it was a living, breathing metropolis. Imagine walking through the Ishtar Gate, its bricks glazed a deep cobalt blue, decorated with striding lions, dragons, and bulls — symbols of the gods. This gateway led into the Processional Way, a grand avenue used during religious festivals when statues of the gods were paraded through the city.

Inside, the streets buzzed with merchants selling spices, wool, grain, and exotic goods from as far as India and Egypt. Scribes sat at corners, ready to write contracts in cuneiform for those who could not. Priests performed rituals in the temples, ensuring the favor of Marduk. Scholars studied astronomy and mathematics in the shadow of the city’s towering ziggurat, Etemenanki — believed by some to have inspired the biblical story of the Tower of Babel.

Fun fact: Babylonian astronomers were so advanced that they could predict lunar eclipses with remarkable accuracy. Their records formed the foundation for later Greek and Islamic astronomy.

But life wasn’t idyllic for everyone. The grandeur of the city masked the harsh realities of social hierarchy. Slaves worked in the fields and households; artisans labored in workshops for powerful elites. Still, compared to many contemporary states, Babylon’s legal system — thanks to Hammurabi’s legacy — offered some protections, even for the lower classes.

The Fall of the Lion

For centuries, Babylon had been the jewel of Mesopotamia, a city whose very name evoked power and majesty. But like all empires, it stood on shifting sands. By the mid-6th century BCE, the rising Persian Empire under Cyrus the Great had become an unstoppable force, and Babylon was its ultimate prize.

The city’s defenses were legendary. Gigantic walls ringed its heart, gates barred every approach, and the Euphrates River ran directly through it, acting as both lifeline and moat. A direct assault would have been suicide. Cyrus knew this — and chose cunning over brute force. His general, Gobryas, orchestrated one of the most ingenious captures in ancient history: the Persians diverted the Euphrates into a side channel, lowering the water level until soldiers could march along the exposed riverbed under the cover of night.

The Babylonians, confident in their walls, were unprepared. By dawn, the invaders were already inside. There was little resistance, no great battle; it was almost as if the city had been taken in its sleep.

Cyrus entered not as a destroyer, but as a restorer. The famous Cyrus Cylinder — sometimes called the world’s first human rights charter — records his pledge to respect Babylon’s gods, repair temples, and return displaced peoples to their homelands. Among those freed were the Jews who had been exiled to Babylon decades earlier. To them, Cyrus was a deliverer. To history, he was the man who turned the lion into a jewel in his crown.

Babylon in the Age of the Bible

Babylon’s place in the biblical narrative is unlike any other city’s. For the Hebrews, it was both a literal power and a lasting symbol — a city of wealth, beauty, and brilliance, but also of arrogance and oppression.

In 586 BCE, during the reign of Nebuchadnezzar II, Babylon’s armies besieged Jerusalem. The city fell, Solomon’s Temple was reduced to rubble, and thousands were marched eastward into captivity — the beginning of the Babylonian Exile. For decades, they lived under the shadow of the great ziggurats, praying for their return to Zion. One psalm captures their grief: “By the rivers of Babylon, we sat and wept when we remembered Zion.”

Babylon was not only a setting for tragedy; it was the backdrop for stories of defiance and faith. The Book of Daniel paints vivid scenes in the royal court — the fiery furnace, the writing on the wall, the king humbled by visions. Even centuries later, in the Christian New Testament, “Babylon” became shorthand for the embodiment of worldly corruption and decadence, the great city doomed to fall.

This duality — the real city and the symbolic one — ensured Babylon’s name would echo far beyond its physical ruins. It became an idea, a warning, and a legend all at once.

Alexander’s Dream in the Dust

By the late 4th century BCE, Babylon had long since lost its role as an imperial capital, but it was still a city of awe. The Persians ruled it now, and for two centuries it had been an important administrative and cultural center within their vast empire. That changed in 331 BCE when Alexander the Great swept through Mesopotamia after crushing the Persian forces at the Battle of Gaugamela.

When Alexander entered Babylon, the city did not resist. Instead, its gates swung open to welcome the young Macedonian king as a liberator. Ancient accounts describe how the streets were filled with garlands, music, and the scent of burning incense. Priests led processions, and the citizens brought offerings as if greeting a god.

For Alexander, Babylon was not just a trophy — it was a vision. He planned to make it the capital of his new, unified empire. In his mind, Babylon’s location was perfect: a crossroads between East and West, the heart of the known world. He envisioned massive construction projects, a new harbor on the Euphrates, and restoration of the towering Etemenanki ziggurat, believed by some to be the biblical Tower of Babel.

But history rarely bends to human ambition. In 323 BCE, at the height of his power, Alexander fell ill in Babylon. Whether from fever, poison, or exhaustion, he died there at just 32 years old. His plans for the city evaporated, leaving only whispers of what could have been. Babylon would never again stand at the center of world power.

The Long Decline

After Alexander’s death, his empire fractured into rival kingdoms. Babylon fell into the hands of the Seleucid dynasty, successors to Alexander in the Near East. They favored a new capital, Seleucia on the Tigris, built just a few dozen miles away. As administrative offices and trade routes shifted, Babylon’s importance withered.

The city’s great temples fell quiet, their priests departed. The Euphrates shifted its course over time, leaving once-bustling harbors stranded. Farmers abandoned the surrounding fields as irrigation canals silted up. By the 2nd century CE, when Roman and Parthian travelers passed through the area, they spoke of ruins more than a living city.

Still, Babylon’s memory never faded entirely. Its walls and gates, even in decay, impressed visitors. Local villages reused its bricks to build their homes, scattering pieces of the ancient capital across the Mesopotamian plain. The Ishtar Gate and Etemenanki crumbled, but in the minds of poets, priests, and chroniclers, Babylon remained immortal — a city of myth as much as history.

The Rediscovery

For centuries, Babylon lay hidden beneath the sands of Iraq, its name preserved more in scripture and legend than in reality. Medieval travelers spoke vaguely of mounds near Hillah, locals pointed to bricks with strange wedge-shaped markings, but the true scale of the city was unknown. It wasn’t until the 19th century that European explorers and archaeologists began to peel back the layers of time.

In 1811, Claudius James Rich, a British resident in Baghdad, conducted one of the first surveys of the site, mapping the mounds and collecting inscribed bricks. But it was the German archaeologist Robert Koldewey who, starting in 1899, undertook a massive excavation that transformed our understanding of Babylon. For nearly two decades, Koldewey’s team unearthed the foundations of palaces, temples, and — most spectacularly — the Ishtar Gate, whose dazzling blue glazed bricks now stand reconstructed in Berlin’s Pergamon Museum.

These discoveries brought the city out of myth and into the realm of archaeology. The inscriptions revealed not just monumental pride, but the mundane life of an ancient city — contracts, receipts, school texts, even love poems. For the first time in over two millennia, the stones of Babylon spoke again.

A Stage for Power in Modern Times

Babylon’s ruins have not been immune to the ambitions of more recent rulers. In the 20th century, Saddam Hussein undertook an ambitious and controversial reconstruction project. Seeking to link his own image to that of Nebuchadnezzar II, he ordered parts of the city’s walls and palaces rebuilt using modern bricks stamped with his name — echoing the ancient practice of marking royal construction.

These restorations were criticized by archaeologists for damaging the original fabric of the ruins, but they also reignited global awareness of Babylon. The city became both a tourist attraction and a political symbol. During the Iraq War in the early 2000s, coalition forces established a military base on the site, causing further harm to the fragile remains. International heritage organizations have since worked to preserve what’s left and mitigate the damage.

Babylon in the Cultural Imagination

Even without its original glory, Babylon’s name resonates. It appears in art, literature, and music, often as a metaphor for opulence, decadence, or moral decay. Reggae musicians sing of escaping “Babylon” as a corrupt modern system; novelists set their stories against its legendary backdrop; filmmakers borrow its imagery to evoke both wonder and warning.

The city also remains a central reference in religious thought. In Christian eschatology, “Babylon” stands as the archetype of the worldly empire opposed to divine truth. In popular culture, it can be both a cautionary tale and a romanticized vision of a lost golden age.

The Enduring Legacy

Today, the ruins of Babylon sit under the scorching Iraqi sun, a UNESCO World Heritage Site since 2019. The outlines of its massive walls still trace the city’s ancient footprint. Visitors walk through reconstructed gates, past mounds that once held palaces, and along pathways that kings, priests, and merchants trod thousands of years ago.

Its survival, even in ruins, is a reminder that cities are more than stone and mortar. Babylon was an idea — of grandeur, ambition, and human creativity — and ideas can outlive empires. The Hanging Gardens may or may not have existed in the form we imagine, but the very fact that we still speak of them shows the city’s power to inspire.

From Hammurabi’s laws to Nebuchadnezzar’s walls, from Cyrus’s conquest to Alexander’s death, Babylon’s story is the story of civilization itself: the rise and fall of human greatness, the persistence of memory, and the enduring pull of a name whispered across time.

Test what you learn today